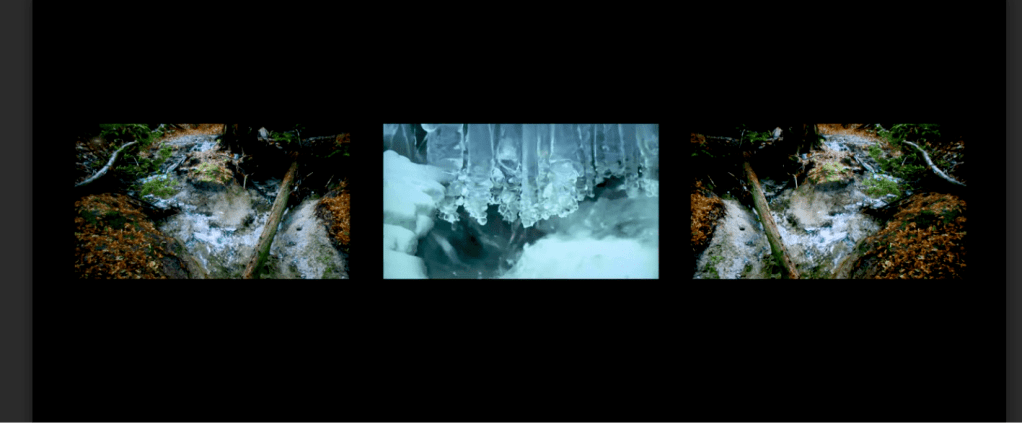

Still image from “Tryptich: Ambient Landscapes” installation, 2019

Ambient Video is video intended to play on the walls in the backgrounds of our lives. In the spirit of Brian Eno’s “ambient music”, Ambient Video must be as Eno says: “as easy to ignore as it is to notice”. For my own work, I expand Eno’s dictum to three interrelated criteria that I want my own ambient video art to meet.

- First, it must not require your attention at any time.

- Second, whenever you do look at it it must reward your attention with visual interest.

- Finally, because ambient pieces are designed to play repeatedly in our homes, offices and public spaces, they must continue to provide visual pleasure over repeated viewings.

The ubiquitous screens in our domestic, corporate and social environments provide rich ground in which ambient imagery can thrive. However, the three criteria for ambient video success are difficult to meet, regardless of venue. Eno saw this problem twenty five years ago when he wrote about his own ambient video art: “These pieces represent a response to what is presently the most interesting challenge of video: how does one make something that can be seen again and again in the way that a record can be listened to repeatedly? I feel that video makers have generally addressed this issue with very little success…”

The problem remains a difficult aesthetic challenge. Some creative avenues are simply inconsistent with ambient experience. Narrative both attracts and relentlessly holds our attention, so most ambient works are essentially non-narrative (although there are some exceptions to this rule – depending on your definition of narrative). Fast cutting also draws attention to itself, so ambient works are generally slower paced.

The most well-known ambient video trope is the venerable “yule log”, which has been burning in video screens on television sets since its introduction at WPIX New York in 1966. The log thrives: it has adapted to every cultural video form since its inception: broadcast television, cable television, satellite TV, VHS tape, DVD, Blu-ray, webcasts, digital files, and executable code. It shares its niche with similar works – such as the many versions of the “video aquarium”, or any number of video websites such as the “eagle-cam” sites dedicated to watching eggs. All of these are indeed ambient video, and they do meet the basic requirements of the form. However, they are kitsch, not art.

However, one can find Ambient Video that can make a claim to being art. I argue that I – and often other ambient video artists – rely on three aesthetic interventions to create ambient art works.

The first is a reliance on strong composition, lighting and cinematography. Since ambient video is slow-paced, the form needs visual compositions that will sustain over exceedingly long screen durations.

The second aesthetic intervention is the direct manipulation of cinematic time. Ambient artists thrive on subjects that present motion in a fixed spot without requiring a camera move to track the subject. Water, clouds, and fire are perfect examples. However the motion of these subjects provide more visual interest if the time base is altered. I typically slowed down water or fire, speed up clouds. In some of my shots, I do both – slow down the water at the bottom of the frame, and speed up the clouds at the top. Cinematic time is therefore treated as plastic – a malleable parameter to be shaped by the artist.

Cinematic space is treated as plastic in an even more intensive fashion. This third aesthetic intervention is far more complex and difficult to achieve – the aggressive use of video layers and layered transitions. In my own work, cinematic space is first fragmented, then recombined. Shots are deconstructed into visual elements, and new elements from the incoming scene are slowly introduced on top of the existing scene, until they completely replace it – and the new shot has been created. This process continues throughout the film, as one landscape forms within and over its predecessor in an endless chain. Each transition occurs in several stages, and each stage is carefully planned, mapped and executed with detailed attention to visual flow and the changing gestalt of the combined outgoing and the incoming shot.